The Effect of the Nord Stream 2 Project on Transatlantic and Euro-Russian Relations

The fact that the President of the United States, Joe Biden, recently acknowledged Vladimir Putin as an “assassin” inevitably impacts European institutions. The harsh statement on Putin poses a primary concern to the EU: it cannot remain a neutral player in the growing tensions between Washington and Moscow. A difficult challenged for Brussels to face for two interconnected reasons. The first issue is in regard to the Nord Stream 2 project between Germany and Russia. The second, is the nature of European treaties, generating a tension between intergovernmental and supranational policy making. Consequently, a stalling occurs, which effects the Union from rapidly evolving into a geo-political leader.

The Nord Stream 2: A Political Move

The German and Russian governments are not far from finishing the Nord Stream 2, an 11 billion-euro pipeline project led by Russia’s state energy Gazprom, predicted to be concluded between 2021 and 2022 . One of the main principles of the pipeline is to go around the Ukrainian territory. Until now, Ukraine has been one of the few countries connecting Russian gas to Europe. The political instability and tension between the Kremlin and the Ukrainian government in the regions of Crimea and Donbass accentuated the will of Putin to economically deprive Ukraine of one of its most important resources (ISPI, 2019). This is a political move to re assert its arbitrary “soft power” on Kyiv, actioned by concluding a deal with the primary political entity -the EU- that Ukraine has been appealing to for protection.

In fact, the Russian economic influence on Europe would most likely prevent the EU, and especially Germany and France, from being inclined to condemn or sanction Russia for future events. Such a scenario would see the USA deprived of its most valuable ally in terms of liberal democratic political principles promoter. Political analysts, like Massimo Gaggi (2021), believe this hesitation on criticizing the Kremlin was already highly visible in February during the visit to Moscow of the High Representative Josep Borrell. During this time the latter failed to condemn Russia on Navalny’s incarceration nor meet with Navalny. There was also no overt defense of the transatlantic relationship, from the attacks of the Russian Minister Sergej Lavrov, regarding US sanctions on Russia.

Impact of Nord Stream 2 on the Current Euro-Russian Trade Relations

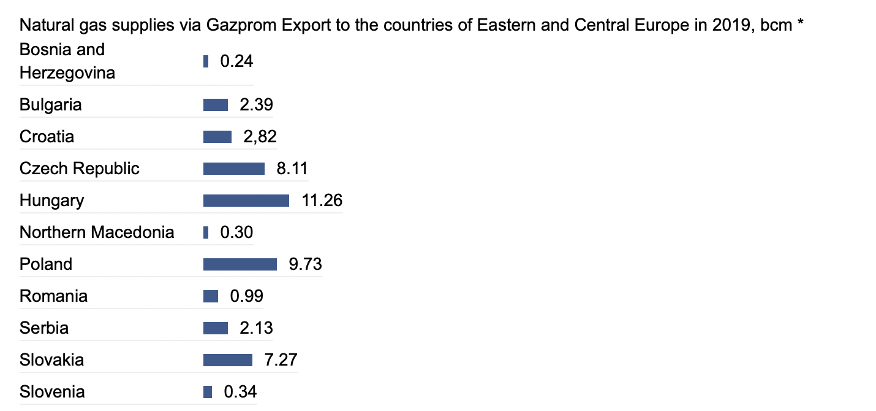

In the case of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, the German government appears convinced to finish the deal. The opposition are primarily the Block of Visegrad: Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland (ISPI, 2019). These are all states that have an economic dependence on Russian products for internal consumption (ISPI, 2019). In 2019, Eastern European countries bought 45.58 bmc (billion cubic meters) of gas supply from Gazprom. For these states, this provided an advantageous position in terms of prices due to the geographical proximity to Russia (Gazprom).

Figure 1: gazpromexport.eu

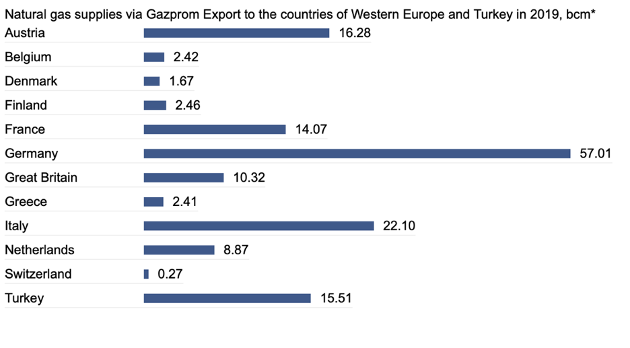

In the same year (2019) Gazprom Export LLC supplied a total of 153,39 bmc of gas to Western European countries. As visible in figure 2, Germany is by margin the main receiver of the gas with 57.01 bcm. The economic deal betweenGermany and Russia generates issues within the EU. It is, first of all, a question of European solidarity. The German Minister of Finance Olaf Scholz sent a letter to the ex-US Secretary of the treasury, Steve Mnuchin, explaining the deal as necessary for the denuclearization process of the country (ISPI, 2015). This explanation did not seem to convince either the Trump delegation at the time, or the Biden delegation today.

Despite the ecological motif, the project would likely increase existing inequalities within the continent. It would increasingly advantage Western Europe (primarily the Franco-German axis), whilst disadvantaging Central Eastern European states in terms of accessibility to a primary resource (ISPI, 2015). This is the opposite of European unity.

Figure 2: gazpromexport.eu

The Nord Stream 2 would enable Russia to transport to Germany 55 bcm per year. Such a deal would see Germany having price conveniences, compared to European colleagues that would then pay the additional cost of transportation. European supranational institutions have proved to be contrary to the project on several occasions. In 2016, the Parliament approved a resolution asking to abandon the project and defining it as “a menace for European security” (EuroParl, 2016). Similarly, the European Commission tried to stop the project on the basis of jurisdictions. Despite this, the Franco-German axis (which would benefit the most from the deal) has remained convinced of the relevance of the pipeline.

The EU’s challenge to Solve Crises above the “Lowest Common Denominator”

This brings us to the ultimate issue the EU is bound to face. The EU, as Sergio Fabbrini (2017) would argue, is stuck in a policy making tension that renders decision making slow and frequently inefficient. In other terms, the supranational entities have limited power in front of the will of member states. On the one hand, the treaties allowed a unitary decision-making process on monetary policies such as the creation of the Euro.

Elements such as Justice and Home Affairs or fiscal policies – that have been tried to be regulated through separate contracts such as the Fiscal Pact in 1997 – remain under state sovereignty (Fabbrini, 2019). This indicates that, to block the project, the Council would be required to unanimously vote against the construction of the pipeline. This is a difficult task to achieve given the singular and especially different interests of states at stake in the project.

Yet the Nord Stream 2 is just the ultimate example of how the EU is stuck in an indecisive and slow policy-making procedure that represents a dramatic anchor for the EU in terms of governance. If tensions will rise and European economic interdependence will be increasingly based on Russia, China and USA it will be extensively complicated to come out of a position of neutrality and turn into an active geo-political actor. In intergovernmental terms, it is likely that one member state will continue to have the ability to veto or prevent changes regarding relationship with third actors. In the construction of a geo-political image, to portray to the world the EU must, for example, appeal to its leadership in promotion of Rule of Law and human rights. These are values that are even enshrined in the TEU and the Copenhagen criteria of 1993 so as to prove the relevance and interest of common cultural values (Gervasoni, 2010). The latter values, in case of neutrality, will be complicated to unite given individual interests and relationships EU states maintain with actors, such as China or Russia.

Individual relationships are fully visible with vaccinations, with states like Hungary or Czech Republic accepting Russian and Chinese independently of the saying of the Commission. These are all cases that lead analysts to suggest that in the future EU’s member states relations with Russia and China may be increasingly individualistic and inevitably generating divisions within the union. A possible future context, that if not faced, may lead the EU to be the economic field of conflict of Great Powers rather than an active Great Power itself.

Conclusion

Biden’s words put the EU in front of a choice to make. On the one hand the Nord Stream 2 pipeline is an ambiguous project that is considered by supranational institutions as risky for the development of European integration. In a geo-political scenario in which rising tensions are once again separating the globe into East and West, what part does the EU want to play? Will it be able to construct a unitary vision on matters such as foreign policy? Will it be able to promote and defend the values of Human Rights and Rule of Law enshrined in Art 2 of the TEU? Or will the EU continue to be a block into an intergovernmental modality of policy making that, as Daniel Kelemen (2017) writes, consistently provides responses to crises to the “lowest common denominator”. The decision over the Nord Stream 2 pipeline may be a first step in understanding in what direction the EU is going and it may be the last chance to prove its primary objective of becoming a leader in the promotion of Human Rights and the Rule of Law.

References:

“Delivery Statistics.” Gazprom Export, www.gazpromexport.ru/en/statistics/.

Europarl. “Texts Adopted – EU Strategy for Liquefied Natural Gas and Gas Storage – Tuesday, 25 October 2016.” Europarl.europa.eu, 25 Oct. 2015, www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2016-0406_EN.html?redirect.

Ferrari, Aldo. “Beyond Ukraine. EU and Russia in Search of a New Relatio.” Ispi, Ispi, 8 June 2015, www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/beyond-ukraine-eu-and-russia-search-new-relation-13424.

Fabbrini, S. (2017). Intergovernmentalism in the European Union. A comparative federalism perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(4), 580–597. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1273375

Fabbrini, S. (2019): Europe’s Future – Decoupling and Reforming, Cambridge University Press, Chapts 1 and 2.

Gaggi, Massimo. “America-Russia: Quale Deterrente?” Corriere Della Sera, Corriere Della Sera, 18 Mar. 2021, www.corriere.it/opinioni/21_marzo_18/america-russia-quale-deterrente-716ae804-8817-11eb-b36f-34a1dcf4e6aa.shtml.

Gervasoni, Carlos. “A Rentier Theory of Subnational Regimes: Fiscal Federalism, Democracy, and Authoritarianism in the Argentine Provinces.” World Politics 62.2 (2010): 302-40. Web.

Gotev, Georgi. “EU Says It Does Not Need Nord Stream 2, but Only Germany Can Block It.” Www.euractiv.com, EURACTIV.com, 24 Feb. 2021, www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/eu-says-it-does-not-need-nord-stream-2-but-only-germany-can-block-it/.

Ispiseo. “Nord Stream 2: Opportunità e Rischi Del Nuovo Gasdotto Di Putin.” ISPI, 7 May 2020,

Kelemen, D. (2017): Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union, Government and Opposition, Vol. 52:2, 211–238.

Smerechynska, Roksolana. “Ukraine at the Crossroads: Still a Victim of Its Powerful Neighbour or Finally Moving towards True Democratic Independence?” Atlas Institute for International Affairs, Titan, 15 Mar. 2021, www.internationalaffairshouse.org/ukraine-at-the-crossroads-still-a-victim-of-its-powerful-neighbour-or-finally-moving-towards-true-democratic-independence/.