The Lack of Negative Liberty and the Growth of Zimbabwe’s Economy

Isiah Berlin’s concept of ‘negative liberty’ describes a classical liberal’s utopia, where people are free from external restraint on one’s actions (Berlin, 1969), whereas positive liberty focuses on the increased role of the state to allow for its citizens to ‘take control of their own lives’. In this essay, I will discuss to what extent a lack of negative liberty does impact the growth of Zimbabwe’s economy. Throughout Western civilization, negative liberty is consistently prescribed through principles such as freedom of speech. In ‘On liberty’ J.S Mill argued that a government’s attack on a competition of ideas and negative freedom prevents the creation of discourse and thus a failure to facilitate societal progression (Mill, 1859)

The lack of free press evident in Zimbabwe is a prime example of the decline of negative liberty which is common throughout Africa. The government’s creation of an echo chamber coherent with a ‘default’ way of thinking has hindered Zimbabwe’s development as a nation. Politicians continue to steal from the state and without the electorate’s freedom to hold them to account, Zimbabwe continues to stagnate economically and socially. The arrests of freelance journalist Hopewell Chin’ono and the leader of Transform Zimbabwe (an opposition party), Jacob Ngarivhume, is a prime example of this. Chin’ono’s article exposing established politicians profiting from ‘massive coronavirus-related financial contracts’ (Independent, 2020) led to him being arrested in July. Whilst Ngarivhume was convicted for ‘inciting violence’ for organisation protests in Harare to criticise the government’s handling of coronavirus. This underlines the suppression of negative liberty, something which Zimbabwe have become accustomed to. The Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front’s actions reject John Rawls’ justification for civil disobedience. Rawls argues that agents engaging in acts of disobedience must do so out of conscientiousness and political motivation to appeal to the common conception of justice (Rawls, 1971). Aggressive policy acting in contrary to Rawls’ principles expose Zimbabwe’s goal of creating a political echo chamber highlighted by blinded conformity to reducing an individual’s negative liberty. However, this has become less commonplace in the post-Mugabe era.

Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s president from 1987 to 2017, was plagued by controversial economic and political reforms which eventually led to hyperinflation which peaked in ‘mid-November 2008 with a rate estimated at 79,600,000,000% per month’ (Cato Journal, 2009). Mugabe’s socialist tendencies meant he focused on government intervention to create liberty in a positive sense. One of the primary causes of their hyperinflation was due to a radical fall in national output which led to food shortages and a current account deficit. All these factors are linked to Mugabe’s decision in 2000 to remove land from white farmers to reverse ‘historical land ownership imbalances that favoured the minority whites’ (Aljazeera, 2020). The redistribution of private property removed the rights of 4000 white farmers in an attempt to create positive freedom for individuals less well off than them. However this had ramifications for their economy, the removal of experienced farmers led to food shortages. Basic economic theory suggests that when necessities are scarce, and demand outstrips supply then there comes a substantial increase in price which risks the possibility of inflation.

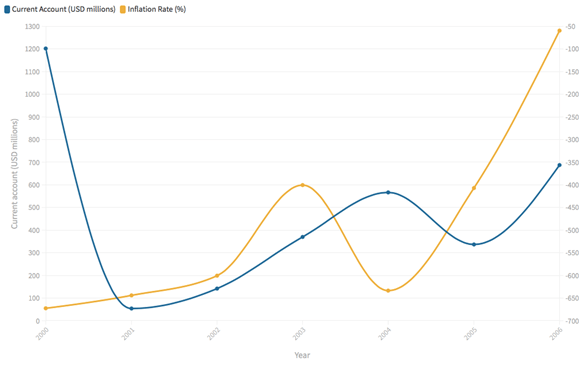

Economist John Anderson found that ‘The land seizures have cost Zimbabwe’s government $1.2bn in tobacco production and exports’. Naturally, this led to Zimbabwe running a current account deficit meaning there was an increased supply of the Zimbabwean dollar in foreign markets. Whilst this would have little to no effect on a fixed exchange rate, Zimbabwe’s floating exchange rate system it led to their dollar depreciating. Mugabe looked towards quantitative easing as a solution to their contracting economy. However, the increase in money supply, food shortages, and fall in exports led to the infamous hyperinflation that destroyed the African nation’s economy. The graph below presents quantitative data associated with Zimbabwe’s current account and inflation rate from 2000 to 2006 displaying how the fall in exports impacted inflation:

The inflation rate went from 55% (2000) to 1281% in 2006, whilst this happened, we can also see how the rate was impacted by Zimbabwe’s trade imbalance. A year after the land reforms were implemented Zimbabwe’s deficit worsened going from -99 (USD millions) to -673 (2000 – 2001). After this year the deficit improved, partly due to farmers gaining more experience in their new roles however the deficit was still considerably worse than prior to the reforms with the deficit still amounting to -531.1 USD million in 2005.

Despite my argument leaning towards the concept that negative liberty and a lack of government intervention equates to a growing economy, there are a plethora of examples that suggest in order to develop a nation from an economic perspective government intervention is needed to allow individuals to take control of their own lives. Technocratic governments remove choice and thus negative liberty based on Betham’s utilitarianism the doctrine that actions are right if they are useful or for the benefit of a majority. This means that a certain government’s decision makes infringe on the extent an individual is able to be free from constraints but with the intention to create economic freedom. After the fall of Silvio Berlusconi’s government in 2011, Mario Monti was appointed to lead a government made up of unelected experts. They implement radical legislation to reduce Italy’s national debt alongside ‘structural reforms to liberate internal markets from the stronghold of state dependence’. Monti’s ability to use austerity measures was due to what sociologist Luigi Pellizoni described as the ability for elites to be ‘suitably protected against the rest of society [..] to perform tasks efficiently’ and thus can be seen as creating positive liberty via utilitarianism which aided Italy’s debt problem during the eurozone crisis.

To conclude, whilst Isiah Berlin’s two concepts of liberty contrast drastically in the way they intend to provide citizens with economic freedom. Where they do align is that they are both inconsistent in their application and to suggest that one creates a growing and stable economy would simply be facetious. Whilst laissez-faire economics and negative liberty have allowed capitalism to blossom throughout liberal democracies across the world, that doesn’t mean positive liberty should be seen as frivolous suggestion when policy is discussed. Italy’s technocratic government is a very clear example of how effective the creation of positive liberty is.

References

Berlin, I., 1969. Two concepts of liberty. Berlin, i, 118(1969), p.172.

“Hanke S., & Kwok, A. (2009) “On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation”, Cato Journal, 29

Mill, J.S., 1975. On liberty (1859).

Rawls, J., 2009. A theory of justice. Harvard university press. Sengupta, K. 2020. How Zimbabwe is clamping down on press freedom. The independent.

Vito. L, 2013. Technocracy’s new bet: Mario Monti runs for premiershiphttps://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/01/20131284454410239.html