The New Energy Cold War

As the UK pursues its green industrial future, control over critical minerals, processing capacity, and global supply chains is emerging as its greatest strategic challenge, with implications for industrial competitiveness, trade relations, and ethical sourcing.

The United Kingdom’s aspiration to become a green industrial powerhouse extends well beyond the deployment of wind turbines and electric vehicles. Increasingly, it hinges on securing reliable access to the critical minerals, advanced technologies, and strategic trade alliances that underpin a sustainable energy future. The transition to net zero is no longer solely an environmental one; it is rapidly evolving into a domain of geopolitical competition. For the UK, this shift entails navigating not only climate targets but also complex strategic dependencies, supply chain vulnerabilities, and diplomatic risks.

Strategic Foundations of the UK’s Green Agenda

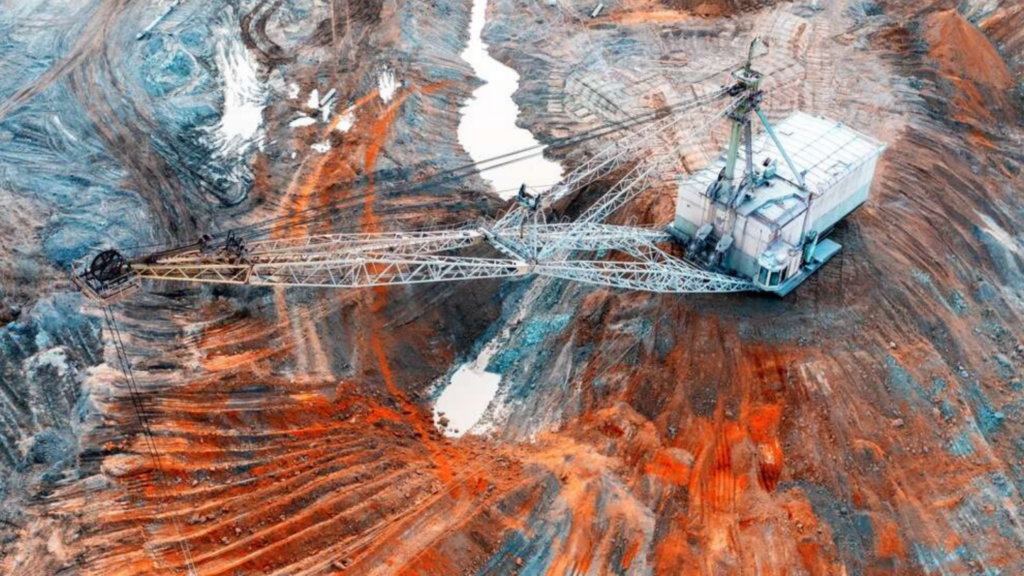

The UK’s green ambitions are embedded within a suite of policy frameworks designed to enhance resource security and industrial resilience. The Critical Minerals Strategy, for instance, outlines commitments to scale domestic extraction, expand recycling capabilities, and foster international collaboration to diversify supply sources and fortify supply chains (GOV.UK, 2023). These efforts are driven by the material demands of clean technologies, including electric vehicles, offshore wind infrastructure, and grid-scale energy storage, all of which rely heavily on minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, and rare earth elements, most of which China primarily dominates the production of, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – China’s refined material production for key energy transition minerals in the base case, 2023-2040 (%).

However, the global geography of these supply chains presents significant strategic challenges. As noted in recent parliamentary analysis, “critical minerals supply is not a geological challenge but a geopolitical one,” with many reserves concentrated in states that are autocratic, non-aligned, or adversarial (UK Parliament, 2023). In essence, the green transition is no longer just a matter of decarbonisation; it is about determining who controls the raw materials and processing capabilities that enable it, and whether the UK can pursue its ambitions without substituting one form of strategic vulnerability for another.

Risk 1: Supply-Chain Vulnerability and Strategic Dependence

One of the most pressing political risks facing the United Kingdom’s green industrial strategy is its reliance on external actors for both the supply of critical minerals and the processing infrastructure required to convert them into usable components. Notably, China currently dominates midstream and downstream processing across many mineral categories, affording it significant leverage over global pricing and export controls (Hill, 2024). For the UK, this risk manifests in two distinct but interconnected dimensions: securing access to raw materials and retaining control over value-added processing. While domestic extraction of minerals such as lithium and tin is technically feasible, the refining, alloying, and manufacturing stages remain overwhelmingly offshore. Without addressing this imbalance, the UK risks missing out on the economic and strategic benefits of what has been described as a “21st-century gold rush” (BBC, 2025b).

Signs of strategic recalibration are already emerging. In early 2025, the UK pursued a minerals cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia aimed at securing long-term supplies of copper, lithium, and nickel (Reuters, 2025), in an effort to diversify sourcing and reduce exposure to geopolitical chokepoints. However, the fragility of global supply chains remains a critical concern. Disruptions—whether caused by export restrictions, trade disputes, or environmental and social opposition in supplier countries—could reverberate across the UK’s green economy. Such shocks risk inflating costs, delaying deployment timelines, and undermining the competitiveness of British clean-tech industries.

Risk 2: Green Industrial Competition & Trade Friction

The global green transition is increasingly characterised by a race for industrial primacy. Governments are deploying a mix of subsidies, mandates, and trade controls to secure clean-tech manufacturing and embed themselves within emerging green value chains. The United Kingdom is actively participating in this shift, with its Levelling Up and Industrial Strategy agendas explicitly linking green investment to regional economic development (Council on Geostrategy, 2021).

However, the international landscape is becoming markedly more contentious. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRM Act) imposes binding obligations on member states to enhance domestic capabilities in mining, processing, and recycling (European Commission, 2023). At the same time, China’s entrenched dominance in critical mineral processing continues to afford it considerable strategic leverage over global supply flows (UK Parliament, 2023).

For the UK, this evolving context introduces trade and diplomatic risks. Should British standards, certification regimes, or supply chain transparency fall behind those of key partners or competitors, the country may encounter elevated costs, restricted market access, or exclusion from preferential trade arrangements. Moreover, the UK faces a delicate balancing act: it must attract inward investment to scale its green industrial base while safeguarding against excessive foreign control over strategic clean-tech assets. This has already become an issue in the UK, as seen in the controversy over Chinese ownership of the Scunthorpe steelworks and the threat of its closure to process imported Chinese-made metal (BBC, 2025a). The event shone a fresh spotlight on Chinese investment in the UK economy, with critics raising questions over potential security risks.

Risk 3: Resource Extraction, Ethics and Reputation

A final, yet often underappreciated, dimension of the green transition is the ethical and reputational risk associated with the extraction and processing of critical minerals. As the pace of green-tech deployment accelerates, so too does scrutiny of the environmental degradation, labour conditions, and social impacts linked to mineral supply chains (Trade Justice Movement, 2025), particularly in regions with weak governance or limited regulatory oversight.

Furthermore, in the UK, civil society campaigns have raised concerns that a significant proportion of the minerals designated as “critical” by the government have limited relevance to the clean-energy transition. Instead, many are argued to serve the defence and aerospace sectors, raising questions about the coherence and transparency of the UK’s critical minerals agenda (Global Justice Now, 2025).

If the UK engages in partnerships or sourcing arrangements with countries where extraction is associated with human rights violations or ecological harm, it risks undermining its credibility as a responsible actor in the global green economy. Such misalignments could trigger political backlash, erode public trust, attract investor scrutiny, and invite diplomatic friction. This would ultimately threaten both the moral authority and industrial competitiveness of the UK’s green strategy.

A Transition with Global Stakes

Britain stands at a pivotal moment. The green transition offers a chance to reinvent its industrial base and to embed new sectors and jobs in regions that, for decades, have lagged behind. But the prize is not guaranteed. The politics of materials, processing, and trade mean that the UK must contend with global power dynamics as much as with carbon budgets.

In the end, the question is not only which technologies Britain deploys, but also whose materials and whose value chains it relies upon. The transition could mark a moment of industrial renewal or a moment of strategic recapture.

Bibliography

- BBC. (2025a). “How much vital UK infrastructure does China own?”. BBC. Published 14th April, 2025. Available at: How much vital UK infrastructure does China own? – BBC News

- BBC. (2025b). “’Huge’ lithium reserves prompts extraction plan”. BBC. Published 2nd June, 2025. Available at: County Durham lithium reserves ‘commercially viable’ – BBC News

- Council on Geostrategy. (2021). “Critical minerals: Towards a British strategy”. Council on Geostrategy. Published 23rd November, 2021. Available at: Critical minerals: Towards a British strategy – Council on Geostrategy

- European Commission. (2023). “European Critical Raw Materials Act”. European Commission. Published 16th March, 2023. Available at: European Critical Raw Materials Act – European Commission

- Global Justice Now. (2025). “Over half of minerals designated as ‘critical’ by UK play ‘no major role’ in green transition, new report says”. Global Justice Now. Published 6th August, 2025. Available at: Over half of minerals designated as ‘critical’ by UK play ‘no major role’ in green transition, new report says – Global Justice Now Global Justice Now

- GOV.UK. (2023). “Resilience for the Future: The UK’s Critical Minerals Strategy”. GOV.UK. Last updated 13th March, 2023. Available at: Resilience for the Future: The UK’s Critical Minerals Strategy – GOV.UK

- Hill, P. (2024). “Strategy and justice: Managing the geopolitics of climate change”. London School of Economics. Published September, 2024. Available at: Strategy-and-justice_Managing-the-geopolitics-of-climate-change.pdf

- Reuters. (2025). “UK to sign critical minerals partnership with Saudi Arabia”. Reuters. Published 14th January, 2025. Available at: UK to sign critical minerals partnership with Saudi Arabia | Reuters

- Trade Justice Movement. (2025). “Civil society calls for UK critical minerals policy to prioritise global justice and environmental protection”. Trade Justice Movement. Published 15th May, 2025. Available at: Civil society calls for UK critical minerals policy to prioritise global justice and environmental protection – Trade Justice Movement Trade Justice Movement

- UK Parliament. (2023). “A rock and a hard place: building critical mineral resilience”. UK Parliament. Published 15th December, 2023. Available at: A rock and a hard place: building critical mineral resilience – Foreign Affairs Committee