Surveillance and Suppression in Post-Coup Myanmar

More than two years after the 2021 coup, Myanmar remains under the rule of a committee of military rulers, known as the Junta. The Junta have been using surveillance and digital repression to silence dissent and block democratic progress. Despite the appearance of electoral processes in the past, Myanmar’s political structure has allowed the military to maintain unchecked power (King, 2022). The armed forces of Myanmar, known as the Tatmadaw, use of technology, including facial recognition, social media monitoring and disinformation campaigns, reflects a dangerous evolution from traditional authoritarian tactics to a modern surveillance state (Dean, 2017). These practices have not only oppressed civil society and political opposition but have also exacerbated existing humanitarian crises.

A Democratic Façade

Since 2011, Myanmar appeared to undergo a transition toward democracy and a market economy. However, this transition was structurally constrained from the beginning. The 2008 Constitution guaranteed military control over three powerful ministries, defence, home affairs, and border affairs, along with ‘25%’ of parliamentary seats and veto power over constitutional amendments (Hlaing, 2012; King, 2022, P.3).

The landslide victory of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in the 2020 elections deepened tensions between the civilian government and the military (King, 2022). On February 1, 2021, General Min Aung Hlaing and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) launched a coup, citing unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud (King, 2022). Despite denials by the Union Election Commission and international election observers such as The Carter Center, the military proceeded to dissolve democratic institutions and assert control (King, 2022).

Myanmar’s Internet Weaponisation Tactics

While the military’s repressive methods are not particularly novel, their technological sophistication has grown. In previous regimes, such as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the secret police, known as the Stasi, relied on informants, wiretaps, and mail interception to control the population (Domínguez, 2024). Today, Myanmar’s intelligence services use tools such as facial recognition, drone surveillance, internet monitoring, and algorithmic tracking to monitor dissent with far greater reach and efficiency (Htwe, 2025).

The Tatmadaw’s Office of the Chief of Military Security Affairs (OCMSA), in coordination with the Myanmar Police Force (MPF) and its intelligence arms, including the Special Branch and the Criminal Investigation Department, operates a highly coordinated surveillance network (Dean, 2017). These agencies not only collect information but actively infiltrate protest groups, civil society organizations, and political parties (Dean, 2017). The result is an environment that discourages civic engagement and erodes basic freedoms.

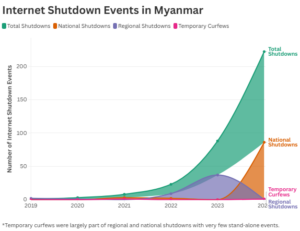

The internet is now a major source of information shaping worldviews and political beliefs. Weaponisation involves using information, true, false, or biased, in ways that cause harm or manipulation (McLoughlin, 2023). Threats can come from individuals, groups, or even AI-powered algorithms and large language models. Digital repression in Myanmar goes beyond passive surveillance. For example, three years since the coup, the Junta have conducted internet shutdowns and telecom jamming ahead of military assaults which fuelled widespread arrests, with thousands of activists, journalists, and civilians detained (See Figure 1) (Htwe, 2025). In addition, the Junta actively deployed disinformation campaigns through state-controlled and fake social media accounts to discredit opposition movements, distort facts, and justify its grip on power (Htwe, 2025).

Internet Shutdown Events in Myanmar

Currently, mobile internet shutdowns, the arrest of elected officials, and the silencing of independent media have become routine (Selth, 2025). Surveillance systems in major cities now include CCTV cameras with license plate and facial recognition capabilities, further expanding the regime’s ability to monitor and intimidate its population (Selth, 2025). Most recently, the Junta banned major Virtual Private Network (VPN) services, cutting citizens off from secure access to blocked apps like Facebook and messaging platforms (Padmanabhan et al., 2021). Authorities also randomly inspect phones under anti-terror laws, seizing VPN apps and detaining users (Padmanabhan et al., 2021). These operations are used below the threshold of war, allowing plausible deniability and making attribution difficult (Coppel and Chang, 2024). Consequently, feedback loops are occurring, where responses are creating secondary threats, leading to echo chambers and escalating tensions.

Civil Conflict and Humanitarian Consequences

Myanmar’s political instability is intertwined with long-standing civil wars, ethnic tensions, and colonial legacies. Military campaigns against ethnic minorities, most notably the ongoing Rohingya conflict that has created a deep-seated humanitarian emergency (Debnath et al.,2022) Additionally, armed clashes in Kachin and Shan states (Figure 2) have caused mass displacement, food insecurity, and the erosion of public services (King, 2022).

International actors should expand sanctions on companies linked to the military and restrict military access to surveillance technology. Additionally, support for international legal mechanisms, including the International Criminal Court and UN investigative bodies, is vital to address war crimes and systemic repression. Finally, tech companies should be vetted and held accountable for enabling surveillance and propaganda in authoritarian regimes. Content moderation and platform transparency must improve in Myanmar’s context.

Myanmar today highlights an example of how authoritarian regimes adapt, merging traditional military control with modern digital surveillance to maintain power and suppress dissent. If left unchallenged, the normalisation of these practices risks entrenching authoritarian rule for future generations. The international community must recognise the evolving nature of authoritarianism and respond with equally adaptive strategies rooted in accountability, protection, and support for democratic resilience.

Bibliography

Coppel , N. and Chang, L.Y.C. (2024). Weaponising the Internet. Springer eBooks, pp.37–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-58645-3_3.

Dean, K. (2017). Myanmar: Surveillance and the Turn from Authoritarianism? Surveillance & Society, 15(3/4), pp.496–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v15i3/4.6648.

Debnath, K., Chatterjee, S. and Afzal, A.B. (2022). Natural Resources and Ethnic Conflict: A Geo-strategic Understanding of the Rohingya Crisis in Myanmar. Jadavpur Journal of International Relations, 26(2), p.097359842211203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/09735984221120309.

Domínguez, P.L. (2024). The State Espionage in the Digital Era: Lessons Learned from the STASI for International Security. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales Grado en Relaciones Internacionales, pp.1–60.

Hlaing, K.Y. (2012). Understanding Recent Political Changes in Myanmar. Contemporary Southeast Asia, [online] 34(2), pp.197–216. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41756341.

Htwe, T.M. (2025). The Role of Intelligence Agencies in Repression and Torture by Myanmar’s Military Junta Intelligence and its Human Rights Abuses During the 2021 Revolution. The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare, 7(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v7i3.6849.

King, A.S. (2022). Myanmar’s Coup d’état and the Struggle for Federal Democracy and Inclusive Government. Religions, [online] 13(7), p.594. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070594.

McLoughlin, I. (2023). A Framework for Understanding the Weaponisation of the Internet. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics (SOLI), pp.1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/soli60636.2023.10425340.

Padmanabhan, R., Filastò, A., Xynou, M., Raman, R.S., Middleton, K., Zhang, M., Madory, D., Roberts, M. and Dainotti, A. (2021). A multi-perspective view of Internet censorship in Myanmar. Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2021 Workshop on Free and Open Communications on the Internet. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3473604.3474562.

Selth, A. (2025). Spy Versus Spy: Myanmar’s Multiple Counterintelligence Challenges. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, pp.1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2025.2453723.