From Agreement to Action: Barriers Facing Global Tax Reform

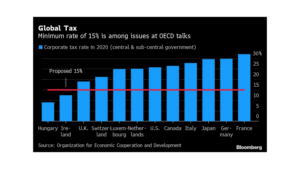

The OECD/G20 Global Tax Agreement, also known as the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), aims to curb tax avoidance and profit shifting. The agreement introduces a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15% (Bunn, 2021). It also reallocates taxing rights over multinational corporations (MNCs). The OECD proposal follows a framework that has been under discussion since 2019. It consists of two main pillars. Pillar One changes where large multinational companies pay taxes. Pillar Two introduces a global minimum corporate tax rate, which is expected to increase global tax revenues by approximately $220 billion (Bunn & Bray, 2025). While it has been praised as a historic breakthrough in international tax reform, the agreement faces major challenges. These include political, institutional, and structural obstacles. Such challenges may limit its implementation and reduce its effectiveness.

Political Commitment and Non-Compliance

Political Commitment and Non-Compliance

As of July 2023, 138 members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework had agreed to implement the global tax deal (OECD, 2023). This represents over 90% of global GDP. However, not all members signed the Outcome Statement. ETAF (2025) stated that countries such as Belarus, Canada, Pakistan, Russia, and Sri Lanka did not sign. Belarus and Russia were suspended from participating in OECD bodies due to geopolitical reasons, and Canada’s refusal was reportedly linked to disagreements over the digital services tax standstill agreement. These non-signatories indicate that some jurisdictions have reservations or face challenges in adopting the agreement.

This uneven commitment weakens the universal application of the agreement and increases the risk of regulatory arbitrage. According to the State of Tax Justice (2023), countries are projected to lose nearly US$5 trillion in tax revenue over the next 10 years. This loss is attributed to MNCs and wealthy individuals utilizing tax havens to evade their fair share of taxation. Research by Cobham and Janský (2018) shows that for OECD members, tax revenue losses amount to 0.66% of GDP, while non-OECD countries are estimated to lose about 1.32% of GDP. OECD countries consistently lose the most tax revenue in absolute terms. The projected future loss of public funds is equivalent to an entire year of global public health spending. In response, the report called on countries to support the start of negotiations on a UN tax convention by voting in favour at the UN General Assembly to prevent these massive losses.

On the other hand, the continued use of tax havens poses a structural risk to the Global Tax Agreement. Even if headline rates are harmonized, complex financial structures like shell companies, special purpose vehicles, and intellectual property licensing can still facilitate avoidance. Without broader transparency and enforcement measures, the new tax rules may simply shift the form of avoidance rather than eliminating it.

U.S. Gridlock and Multinational Tax Avoidance

The United States has played a paradoxical role in shaping and potentially implementing the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). As the home to many of the world’s largest and most profitable MNCs, particularly in the digital and tech sectors, the U.S. is both a key architect of the deal and a possible obstacle to its success. The political posture of the United States significantly influences the deal’s success.

While the U.S. was instrumental in the negotiation process, its domestic ratification faces hurdles. Congressional resistance, particularly among Republicans, has delayed formal adoption (OECD, 2023). The United States, home to many of the affected corporations, has expressed concerns that its domestic tax base may be eroded by foreign claims on American company profits.

Additionally, The White House (2025), cited concerns over national sovereignty and the treatment of U.S. tech firms. Global Tax Deal was labeled as a discriminatory foreign tax practice, arguing that American companies may face retaliatory international tax regimes if the United States does not comply with foreign tax policy objectives.

Political divisions and lobbying by large tech firms, coupled with Republican opposition, have raised concerns that the U.S. may not fulfil its commitment, particularly regarding the reallocation of taxing rights through Pillar One’s “Amount A” mechanism. Amount A targets companies with more than €20 billion in annual revenues and profit margins above 10 percent. For these firms, 25 percent of profits exceeding the 10 percent margin would be taxed in the countries where they have customers, rather than where they are headquartered or produced (Bunn and Bray, 2025). This represents a redistribution of tax revenues from countries where multinational corporations operate to those where they sell their products. U.S.-based companies, such as Google, Apple, Amazon, and Meta, constitute a major share of the affected multinational firms.

As a result, the agreement’s most important impact is on effective tax rates. The effective tax rate is the actual rate at which a corporation pays after accounting for deductions, exemptions, and loopholes. It differs from the statutory tax rate, which is the official rate set by law. It is evident that, contrary to the global trend, North America is inclined to reduce this rate.

From a strategic perspective, the U.S. benefits from the current international tax framework, namely, residence-based taxation. This structure allows American MNCs to accumulate and safeguard overseas profits. Consequently, there is resistance among U.S. policymakers and business leaders to shift taxing rights to countries where consumption occurs, particularly emerging and low-income economies.

Conclusion

The United States plays a crucial role in the success of the OECD/G20 Global Tax Agreement due to its global influence and the fact that it is home to most of the multinational corporations targeted by the reforms. However, its internal political divisions, strategic ambivalence, and protection of corporate interests raise doubts about its willingness to fully implement the deal. If the U.S. ultimately fails to implement the deal, the multilateral effort to create a fairer global tax system could collapse. This would reinforce long-standing criticisms that powerful states shape international tax rules to serve their interests. For developing countries, such a scenario highlights deep concerns about unequal commitments and persistent power imbalances in global economic governance.

References

138 countries and jurisdictions agree historic milestone to implement global tax deal. OECD. (2023). https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2023/07/138-countries-and-jurisdictions-agree-historic-milestone-to-implement-global-tax-deal.html

Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). OECD. (2025). https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/base-erosion-and-profit-shifting-beps.html

Bunn, D. (2021, December 19). What do global minimum tax rules mean for corporate tax policies?. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/blog/oecd-global-minimum-tax-rules/

Bunn, D., & Bray, S. (2025, February 27). The latest on the Global Tax Agreement. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/blog/global-tax-agreement/

Cobham, & Jansky. (2018). Global distribution of revenue loss from tax avoidance: Re-estimation and country results. Eutax. https://www.taxobservatory.eu/repository/global-distribution-of-revenue-loss-from-tax-avoidance/

The State of Tax Justice 2023. Tax Justice Network. (2023, August 30). https://taxjustice.net/reports/the-state-of-tax-justice-2023/

The United States Government. (2025, January 21). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) global tax deal (global tax deal). The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/the-organization-for-economic-co-operation-and-development-oecd-global-tax-deal-global-tax-deal/

Weekly Tax News – Monday 17 July 2023. ETAF. (2023). https://etaf.tax/weekly-tax-news-monday-17-july-2023/