Rare Earths, Intelligence and National Security: How China’s Restrictions Threaten U.S. Defense Resilience and Risk a New Trade War

China’s 2025 rare earth export restrictions reveal how economic leverage has become a core tool of modern warfare, exposing U.S. defense vulnerabilities and reshaping the rules of global power.

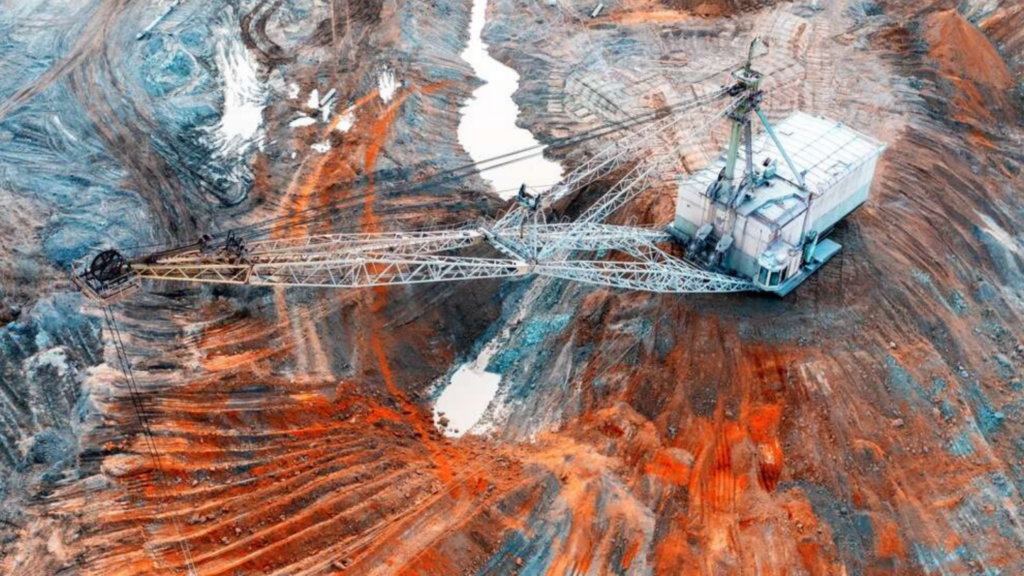

In 2025, China reasserted its dominance over the global supply of rare earth elements (REEs) by introducing new export restrictions on several critical materials used in military and advanced technological systems. While this move was officially framed as regulatory modernization, analysts in Washington and allied capitals quickly interpreted it as a strategic maneuver, one that exposes deep vulnerabilities in the United States’ defense supply chain and signals the opening of a new front in great-power competition. The implications extend far beyond trade or industry; they penetrate the domains of intelligence, security, and strategy.

China’s Rare Earth Monopoly as Strategic Leverage

Rare earth elements, a group of 17 minerals essential for high-tech manufacturing, form the backbone of modern defense capability. From guidance systems in missiles to jet engines and radar arrays, they are indispensable to military superiority. According to Al Jazeera (2025), China controls around 70% of global mining and nearly 90% of the processing capacity for these elements, making it the undisputed gatekeeper of global supply chains.

This dominance was never accidental. For decades, Beijing pursued a deliberate resource industrial policy, coupling subsidies and environmental flexibility with foreign technology acquisition. As The Week (2025) reported, “virtually all global rare earth production runs through China,” meaning that U.S. firms remain dependent even when ores originate elsewhere. Such concentration gives China not only economic advantage but also strategic leverage — the power to use materials as a geopolitical weapon.

Intelligence analysts now view China’s REE monopoly as a tool of “economic statecraft,” a form of coercive leverage similar to energy politics in the Cold War. When Beijing imposes export licensing or quota restrictions, it sends signals to competitors and adversaries that it can impose non-kinetic deterrence: the ability to degrade a rival’s defense readiness without military confrontation (Meng, 2025).

Economic Intelligence and Supply Chain Vulnerability

From an intelligence perspective, REEs highlight the blurred lines between economic and national security intelligence. U.S. intelligence agencies and defense planners increasingly rely on supply chain intelligence (systematic mapping of industrial dependencies) to anticipate coercion risks.

As Reuters (2025) reported, China’s new export controls require special licenses for elements like dysprosium, terbium, and scandium, all essential in high-performance magnets and guidance systems. These changes create “information asymmetry”: China’s opaque licensing process makes it difficult for foreign intelligence agencies to predict supply flow, prices, or which Western contractors may be targeted for delays. The lack of transparency itself becomes an intelligence challenge.

Intelligence agencies must thus track:

- Production and stockpile data: assessing how much material the U.S. or allies possess and how long defense manufacturing could continue if supply stops.

- Corporate networks and intermediaries: many REE refiners are subsidiaries of Chinese state-owned firms operating abroad.

- Policy signaling: Beijing’s use of export restrictions as political messaging before major geopolitical events such as the G20 Summit or U.S.–China trade talks.

Such analysis represents the growing field of geo-economic intelligence, fusing trade, technology, and industrial data with traditional threat analysis. In this case, rare earths are both an economic and a security intelligence issue.

Industrial Security and Defense Preparedness

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has repeatedly acknowledged that its industrial base depends on foreign supply chains vulnerable to “strategic choke points.” The Guardian (2025) and Axios (2025) both highlight that the U.S. defense sector relies on China for 72% of some rare-earth inputs, including those used in the F-35 fighter jet, naval radar systems, and missile actuators.

From a national security viewpoint, this creates a window of vulnerability that adversaries could exploit through timing or selective restriction.

Intelligence Diplomacy and International Coordination

Another key implication is the emergence of intelligence diplomacy: cooperative monitoring and policy coordination between allied nations to secure strategic resources. The U.S.–Australia critical minerals agreement signed in October 2025 (AP News, 2025) and ongoing G7 discussions on rare-earth diversification demonstrate a new era of intelligence sharing beyond traditional military threats.

Allied intelligence services are increasingly sharing:

- Production and trade data to track Chinese influence in global supply chains

- Technological intelligence related to refining and magnet production

- Early-warning signals of export disruptions or resource nationalization

In effect, REE intelligence has become part of the broader collective security architecture, similar to NATO information sharing during the Cold War but focused on supply chains rather than troop movements.

Non-Kinetic Warfare and Strategic Deterrence

Beijing’s control over REEs exemplifies a form of non-kinetic warfare, the ability to achieve strategic objectives without direct military confrontation. Meng (2025) describes this as “strategic deterrence via supply disruption,” where economic actions generate military disadvantage for the adversary. Unlike cyber or nuclear deterrence, the weapon here is economic dependency.

For the U.S., this means national security threats are no longer confined to battlefields but embedded within industrial ecosystems. Rare-earth restrictions can slow weapons production, delay maintenance, or undermine modernization programs, which degrades capability without a single missile being launched.

Intelligence agencies, therefore, must adapt analytic frameworks to detect and counter economic coercion early. Predictive models integrating trade data, satellite imagery of mining operations, and machine-learning forecasts of policy shifts could help anticipate such non-kinetic attacks.

The Risk of a Renewed Trade War

China’s REE restrictions also raise the prospect of a renewed U.S.–China trade war, but this time with direct defense implications. As South China Morning Post (2025) noted, Washington is “stepping up global rare-earths hunts” despite tentative trade agreements, while Beijing accuses the U.S. of weaponizing technology policy. These tensions illustrate how economic policy and national security have become inseparable.

Should the U.S. respond with tariffs, sanctions, or export bans on Chinese technologies (for instance, in semiconductors or AI), China may escalate by further tightening rare-earth exports. Such tit-for-tat measures would not only harm trade but also strain intelligence cooperation, increase misinformation risks, and raise uncertainty for defense readiness planning.

China’s rare-earth restrictions mark a turning point in how intelligence and security must be conceptualized in the 21st century. What once seemed a supply-chain issue now sits at the core of strategic deterrence, industrial resilience, and non-kinetic warfare. For intelligence communities, the challenge is twofold: to anticipate economic coercion and to secure the technological base upon which national defense depends.

The REE confrontation between China and the U.S. is not merely about minerals — it is about information dominance, strategic leverage, and the future of industrial power. Unless Washington and its allies invest heavily in economic intelligence, resource diversification, and joint industrial security, they risk fighting the next great-power competition not on the battlefield but in the supply chains that feed it.

Bibliography

- Al Jazeera, 2025. Despite US push, China poised to dominate rare earths for years, 21 October.

- Associated Press (AP News), 2025. US and Australia sign critical-minerals agreement as a way to counter China, 20 October.

- Meng, W., 2025. Expert Insight-Based Modeling of Non-Kinetic Strategic Deterrence of Rare Earth Supply Disruption. arXiv.

- Reuters, 2025. China blames US for global panic over rare earths controls, 16 October.

- South China Morning Post (SCMP), 2025. US stepping up global rare earths hunt despite China trade agreement, 10 November.

- The Guardian, 2025. US reaches deal with China to speed up rare-earth shipments, White House says, 27 June.

- The Week, 2025. Why the US needs China’s rare earths, 21 April.