A Message to Europe: Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Future Lies to the East

Summary

Kazakhstan chooses Russian firm Rosatom and Chinese state reactors for its first nuclear construction since the Soviet era, deepening its position in the non-Western geopolitical sphere, reducing European hopes for future integration in the short term, and indicating that Europe may face diminishing returns in Central-Asian ‘Middle’ power states.

Rationale

After Kazakhstan’s nuclear power referendum in October 2024, where the citizenry voted overwhelmingly ‘for’ nuclear power after decades of discussions and lobbying, it is unsurprising that the 2 proposed nuclear reactor projects have begun. The Central Asian country has been a major power in the production of nuclear fuels and technology over the last 50 years, boasting 14% of the world’s uranium resources (in 2024) and producing over 40% of the global uranium production (World Nuclear Association, 2025a). Kazakhstan itself, however, is an energy importer and one in a small crisis – its existing infrastructure is a legacy of the Soviet era and is largely worn-out, meaning the state was forced to import nearly 15% of its electricity in 2023, an increase of 500% from 2022 (Kassenova, 2024), largely from Russia.

While the advent of the nuclear energy project is hopeful, it will not solve these electricity woes in the short term, given a minimum of 10-year build timeframe, as well as nuclear reactor projects being notorious for overrunning timescales – 40% of the current reactors under construction are overrunning by at least 1 year (WNISR, 2025).

Nuclear Energy

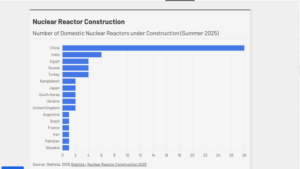

Kazakhstan has selected Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy corporation Rosatom to build the first project and has appointed China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), also state-owned, for the second project over bidders from France and South Korea (Vaal, 2025). This is indicative of the wider environment of delivery expertise, where China dominates nuclear reactor production numbers domestically, accounting for a huge proportion of the current global projects.

While Russia is currently only building 4 reactors domestically, it is the leading global figure in the international market, with nearly 20 current construction projects in China, Egypt, India, Turkey, Bangladesh, Iran, and Slovakia (WNISR, 2025).

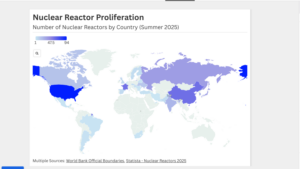

Further, the geographic spread of nuclear power generation systems worldwide forms into two broad cleavages of the ‘West’ and ‘East’, as represented in Figure 2. However, these cleavages are on two very different trajectories regarding integration into their energy supply. Non-Western states are capitalising on advances in nuclear generation system technologies for new reactors, whereas Western states’ provision is swiftly declining. As of 2025, 213 nuclear reactors have been closed worldwide, with 62% of these coming from Europe. Accounting for the traditional 40-year lifespan of the infrastructure, a further 120 reactors will close by 2030, primarily in Western states (WNISR, 2025).

Balancing Act

This procurement highlights Kazakhstan as a middling power, possibly shifting towards ‘Eastern’ great power spheres of influence and slightly diverging from its multi-vector diplomatic strategy. Despite growing openness to the EU and Europe more generally regarding trade, with the EU being Kazakhstan’s largest export region—Italy alone accounting for 28.1%—the country remains heavily dependent on Chinese and Russian imports (32.2% and 27% respectively) (Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National Statistics, 2025). Beyond trade economics, its strategic engagement with Russia and China should give Europe pause for thought about further integration.

European investment has been significant and substantial in recent years, with Kazakhstan expressing its desire to develop a growing partnership with the bloc, particularly as a key exporter of uranium to France, where roughly 70% of electricity generation is nuclear-powered (World Nuclear Association, 2025b). Key events such as the Astana International Forum (AIF) and the inaugural EU-Central Asia Summit (‘Samarkand Summit’) demonstrate a concerted effort with public diplomacy on both sides to build strategic relationships in energy, trade, and investment (Zajmi, 2025a). Europe committed $10 billion to the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor (TITR) in 2024, along with an additional $12 billion through the Global Gateway Investment Package following the Samarkand event (Zajmi, 2025b), bringing total investments to more than $180 billion since 2005 (Zajmi, 2025c).

Despite the investment, the purchase of Russian and Chinese reactors shows it is not so easy to supplant an entrenched relationship. Russia, through Rosatom, already owns 26% of Kazakhstan’s uranium deposits and has a major shareholder position in Kazatomprom, suggesting deep ties to Moscow (Paquette and Shin, 2025). As an ex-Soviet state and a key member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the shadow of Russian leverage is always present. Also, any advances in integration or infrastructure from European investment via the Trans-Caspian routes benefits China (and many of the 5,500 Chinese companies in the country) as a thoroughfare of the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) middle section and so any benefits are shared between the global powers (Kasantsev-Vaisman, 2025).

Kazakhstan had the opportunity to make a statement and engage further with French partners for this procurement and so tie its energy future towards Europe, but has not chosen to do so. There are obvious mitigations to the choice, based on the capacity and efficacy of Sino-Russian domination in the market, but Europe may need to think again about how much influence it can generate over a country so intrinsically linked to its major threats, and how failure to win over contested markets can be perceived for the bloc’s future. Given how much agency Kazakhstan has today in playing the multi-vector diplomat, it will sting more.

References

- Kassenova, T. (2024). Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Power Conundrum. The Diplomat [online]. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2024/10/kazakhstans-nuclear-power-conundrum/. (accessed: 26 June 2025).

- Kazantev-Vaisman, A. (2025). Kazakhstan’s Policy of Diversifying the Routes of Energy Supplies to Europe: Interests of Israel and the EU. The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies – Bar-Ilan University [online]. Available at: https://besacenter.org/kazakhstans-policy-of-diversifying-the-routes-of-energy-supplies-to-europe-interests-of-israel-and-the-eu/. (Accessed: 26 June 2026).

- Paquette, J., Shin, F. (2025). Kazakhstan’s nuclear future runs through Europe. Available at: https://neweasterneurope.eu/2025/02/27/kazakhstans-nuclear-future-runs-through-europe/. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

- Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National Statistics. (2025). Foreign trade turnover of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available at: https://stat.gov.kz/en/industries/economy/foreign-market/publications/332481/. (accessed: 26 June 2025).

- Vaal, T. (2025). Russia’s Rosaton, China’s CNNC to lead consortiums to build first nuclear power plants in Kazakhstan. Reuters [online]. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russias-rosatom-lead-consortium-build-first-nuclear-power-plant-kazakhstan-2025-06-14/. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

- WNISR (World Nuclear Industry Status Report). (2025). World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2024. Available at: https://www.worldnuclearreport.org/World-Nuclear-Industry-Status-Report-2024. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

- World Nuclear Association. (2025a). Uranium and Nuclear Power in Kazakhstan. Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/kazakhstan. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

- World Nuclear Association. (2025b). Nuclear Power in France. Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/france. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

- Zajmi, X. (2025a). Samarkand Summit sees EU deepen Central Asia strategic relations. Euractiv [online]. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/samarkand-summit-sees-eu-deepen-central-asia-strategic-relations/. (Accessed 26 June 2025).

- Zajmi, X. (2025b). Kazakhstan’s economic diversification strategy has EU market front and centre. Euractiv [online]. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/kazakhstans-economic-diversification-strategy-has-eu-market-front-and-centre/. (Accessed 26 June 2025).

- Zajmi, X. (2025c). China and Russia score big in Kazakhstan, leaving Europe on the sidelines. Euractiv [online]. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/china-and-russia-score-big-in-kazakhstan-leaving-europe-on-the-sidelines/. (Accessed 26 June 2025).