Might is Right: Will the Philippines Accept It?

Introduction

“The standard of justice depends on the equality of power to compel and that in fact the strong do what they have the power to do and the weak accept what they have to accept,” said the Athenians to the Melians in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. When the city of Melos chose to become neutral in a power rivalry between Athens and Sparta, the story ended terribly with Athens razing Melos to the ground in 416 BC. This piece of strategic history is relevant for the Philippines amid a great power competition between its security ally, the United States against a giant South China Sea claimant neighbor, China.

In a world where uncertainty is for certain, states maximize their relative power over others to survive in the international system. While the pursuit of justice in domestic politics is important to build strong institutions, the international system does not work that way. Instead, the Philippines must realize that “might is right” to survive by investing in conventional war capabilities appropriate to the archipelago and beyond.

A Fight to be Right

Under Former President Benigno Aquino III, the Philippines fought a good-versus-evil phenomenon. Manila deferred to its security alliance with the US and international law in upholding its claims in the West Philippine Sea in the greater South China Sea against Beijing, even equating Chinese domination to Nazi expansion of Europe in the late 1930s.

On a fair note, the Chinese rise prompted the Philippines to modernize the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Through the Revised AFP Modernization Program in 2012, Manila sought to shift the organization from internal security operations to external defense missions in a joint nature by transforming the organization and doctrine and investing in resources and capabilities.

Despite the modernization program’s existence, the Philippine Congress refused to robustly prioritize the defense budget, where it fluctuated drastically for the first five years. With gaps between the policy and the budget, the AFP’s external defense posture did not gear credibility for a conventional war capacity but only guaranteed modest border patrol. Renato De Castro observes that modest efforts are likely attributed to the Philippines’ deference to American power in the region.

Under Barack Obama’s tenure, the US launched a rebalancing strategy of pivoting to Asia in 2012 to contain China’s rise, allotting 60 percent of its military assets in East Asia. In this course, the US went at great lengths to consolidate its network of regional alliances and partnerships, including the Philippines. In 2014, Washington and Manila signed the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) which upgrades the security alliance by allowing American troops for a rotational presence in the Philippines as they enhance interoperability and training and exercise through the annual Balikatan Exercises with the AFP.

The US also regularized its Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) program in the South China Sea to protest China’s detrimental behavior. The Philippines hoped that aside from EDCA and American FONOPS, the US would provide more substantial support to defend its claims in the West Philippine Sea. But the Obama administration has been giving mixed signals. While Washington supports stability and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, it also tells the claimants to settle their disputes peacefully through appropriate forums regarded by international law since they are a neutral party.

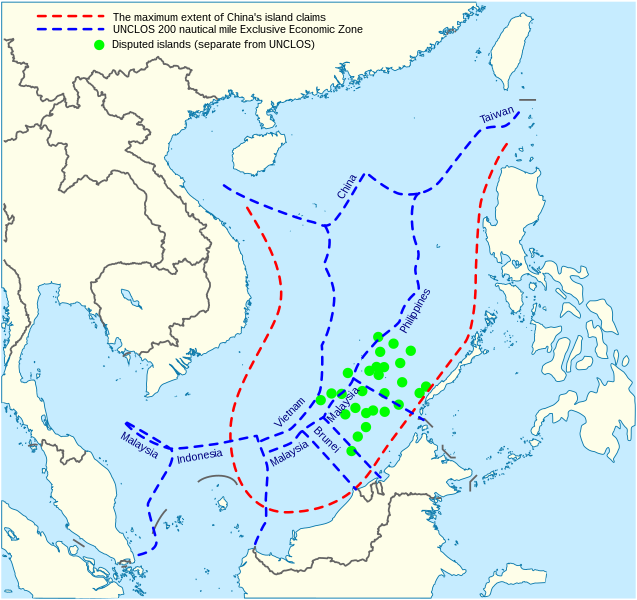

Manila rallied a global opinion for its moral crusade against Beijing. In 2013, the Philippines has taken its territorial dispute with Beijing in the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) at The Hague. Conversely, China refused to adhere to the PCA’s jurisdiction by nonparticipation and repudiated the award it gave to the Philippines in 2016, arguing that it cannot force states to comply with an ad hoc arbitration.

Right Went Wrong

During Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency, the Philippines’ moral high ground came into question with his independent foreign policy that later transformed into an appeasement policy with China. Duterte argued that unless the people were ready for war, engaging China (such as by joining Belt and Road Initiative’s investment projects to support the state’s developmental needs, despite economic security risk) remains the most promising option.

Duterte’s refusal to personally endorse the 2016 Arbitral Ruling pushed the Philippines’ legal options to the sidelines and allowed China to spell a legal definition in the South China Sea through the crafting of a long-overdue ASEAN-China Code of Conduct. It additionally paved the way for possibilities for joint exploration in the Spratly Islands.

Furthermore, the security alliance with the US hangs in the balance with Duterte’s tirades against American criticism on his infamous war on drugs and his pivot to China. In February 2020, Duterte terminated the 1997 Visiting Forces Agreement which provided legal definitions on the presence of US armed force personnel in the country, over Washington’s disenfranchising of his political ally’s travel visa.

Current US President Donald Trump – known for his respite on the unfair burdens of the alliance system and international institutions – said that he did not mind Duterte’s pronouncement. This phenomenon may seem disconnected as Trump, unlike Obama, transformed the US-China relations into a strategic competition by increasing the number of FONOPS and engaging its regional allies and partners for a free and open Indo-Pacific.

But in June this year, Duterte changed his mind by suspending the VFA’s termination over “political developments in the region”. In the weeks that followed, ASEAN upheld the UNCLOS, the Philippines finally asserted the 2016 ruling, followed by US support, and the Philippines agreed upon a rules-based order and the tap of the US for assistance in case of armed confrontation with China in the South China Sea.

Some argue that this suspension provides breathing room for the alliance, notably given the above-mentioned developments. But so long as Duterte is in power, the alliance will still be the least promising option. In this sense, the Philippines has lost credibility to become a frontier against Chinese revisionism.

In the middle of a global pandemic, China and the US have taken a severe level of competition where the Philippines has no choice but to confront it. China has tested its conventional war capability by launching its “aircraft carrier destroyer” medium-range ballistic missiles in the South China Sea, while the US has consolidated its network as well as improved its posture in the Pacific. Assuming that China continues to rise, a security competition with the US will perpetuate for the next few decades, and the Philippines cannot insist on neutrality. Even if its newest assets arrive and naval patrols continue, the lack of strategic rationale for a geopolitical consideration might render tactical, operational, and logistical efforts futile.

Capturing its Might

In the 2022 elections, the general public’s discontent over Duterte’s foreign policy may trigger a crusade in favor of the Philippines’ national interests. However, there is a risk of repeating the tragedy of wanting to be “right” and discarding “might”. From a commonsensical analysis, following the same method while expecting a different outcome is problematic for states trying to survive in the international system. The strategic continuity of the Melian Dialogue provides enough explanation that the Philippines should capture its might, based on action.

Compelling the enemy to one’s will requires a strong military that is invested for conventional war scenarios, such as precision-strike capabilities in the air-sea-land operational environment fitted for the archipelago, while also invested in cyber and nonmilitary investment. But this requires lots of money, which is why the defense budget should be given prime importance, along with other constitutional priorities, like education and health, in the annual general appropriations.

It also needs like-minded and capable defense partners like Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, India, and Australia, Germany, and France, aside from its traditional ally to complement the limits of its power in the short to the long-term range, not for dependence, but a shared vision. Once all these are in place, Manila has the leverage to enforce its legal victory and shape the environment to its liking. As Doug Bandow has said, “Let Filipinos upgrade their military, develop, regional allies, and accept responsibility for their own future.”